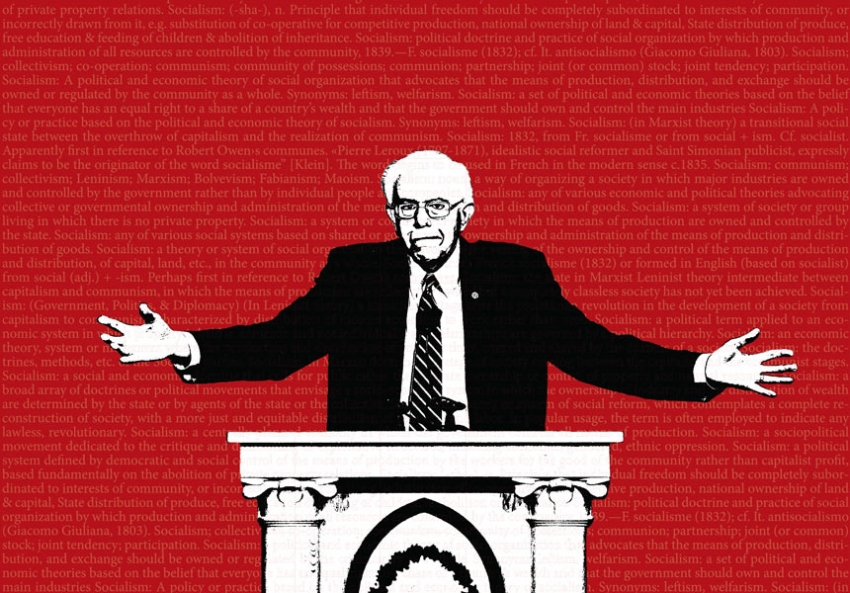

The Sanders campaign is resurrecting socialist electoral politics and paving the way for a more radical public discourse.

Socialism. For most of recent U.S. history, the word was only used in mainstream discourse as invective, hurled by the Right against anyone who advocated that the government do anything but shrink, as anti-tax advocate Grover Norquist once put it, “to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub.”

How is it, then, that Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), a democratic socialist, has repeatedly drawn

crowds in the thousands or tens of thousands in cities and towns throughout the nation and is within striking distance of Hillary Clinton in

Iowa and

New Hampshire? In a country that’s supposed to be terrified of socialism, how did a socialist become a serious presidential contender?

Young people who came to political consciousness after the Cold War are less hostile to socialism than their elders, who associate the term with authoritarian Communist regimes. In a

Pew poll from December 2011, 49 percent of 18-to-29-year-olds in the United States held a favorable view of socialism; only 46 percent had a favorable view of capitalism. A

New York Times/CBS News survey taken shortly before Sanders’ Nov. 19, 2015,

Georgetown University speech on democratic socialism found that 56 percent of Democratic primary voters felt positively about socialism versus only 29 percent who felt negatively. Most of those polled probably do not envision socialism to be democratic ownership of the means of production, but they do associate capitalism with inequality, massive student debt and a stagnant labor market. They envision socialism to be a more egalitarian and just society.

More broadly, a bipartisan consensus has developed that the rich and corporations are too powerful. In a

December 2011 Pew poll, 77 percent of respondents (including 53 percent of Republicans) agreed that “there is too much power in the hands of a few rich people and corporations.” More than 40 years of ruling class attacks on working people has revived interest in a political tradition historically associated with the assertion of working class power—socialism.

But at this point in American politics, as right-wing, quasi-fascist populists like Donald Trump, Ted Cruz and others of their Tea Party ilk are on the rise, we also seem to be faced with an old political choice: socialism or barbarism. Whether progressive politicians can tap into the rising anti-corporate sentiment around the country is at the heart of a battle that may define the future of the United States: Will downwardly mobile, white, middle- and working-class people follow the nativist, racist politics of Trump and Tea Partiers (who espouse the myth that the game is rigged in favor of undeserving poor people of color), or lead a charge against the corporate elites responsible for the devastation of working- class communities?

This may be the very audience, however, for whom the term socialism still sticks in the craw. In a

2011 Pew poll, 55 percent of African Americans and 44 percent of Latinos held a favorable view of socialism—versus only 24 percent of whites. One might ask, then: Should we really care that the term “socialism” is less radioactive than it used to be? With so much baggage attached to the word, shouldn’t activists and politicians just call themselves something else? Why worry about a label as long as you’re pursuing policies that benefit the many rather than the few? Is socialism still relevant in the 21st century?

Fear of the ‘s’ word

To answer this question, first consider how the political establishment uses the word. The Right (and sometimes the Democrats) deploy anti-socialist sentiment against any reform that challenges corporate power. Take the debate over healthcare reform, for example. To avoid being labeled “socialist,” Obama opted for an Affordable Care Act that expanded the number of insured via massive government subsidies to the private healthcare industry—instead of fighting for Medicare for All and abolishing private health insurers. The Right, of course, screamed that the president and the Democratic Party as a whole were all socialists anyway and worked (and continues to work) to undermine efforts to expand healthcare coverage to anyone.

But what if the United States had had a real socialist Left, rather than one conjured up by Republicans, that was large, well-organized and politically relevant during the healthcare reform debate? What would have been different? For one thing, it would have been tougher for the Right to scream “socialist!” at Obama, since actual socialists would be important, visible forces in American politics, writing articles and knocking on doors and appearing on cable news. Republicans would have had to attack the real socialists—potentially opening up some breathing room for President Obama to carry out more progresssive reforms. But socialists wouldn’t have just done the Democrats a favor—they would also demand the party go much further than the overly complicated and insurance company friendly Obamacare towards a universal single-payer healthcare program. The Democrats needed a push from the Left on healthcare reform, and virtually no one was there to give it to them.

What is democratic socialism?

So what do we mean by “democratic socialism”? Democratic socialists want to deepen democracy by extending it from the political sphere into the economic and cultural realms. We believe in the idea that “what touches all should be governed by all.” The decisions by top-level corporate CEOs and managers, for example, have serious effects on their employees, consumers and the general public—why don’t those employees, consumers and the public have a say in how those decisions get made?

Democratic socialists believe that human beings should democratically control the wealth that we create in common. The Mark Zuckerbergs and Bill Gateses of the world did not create Facebook and Microsoft; tens of thousands of programmers, technical workers and administrative employees did—and they should have a democratic voice in how those firms are run.

To be able to participate democratically, we all need equal access to those social, cultural and educational goods that enable us to develop our human potential. Thus, democratic socialists also believe that all human beings should be guaranteed access, as a basic social right, to high-quality education, healthcare, housing, income security, job training and more.

And to achieve people’s equal moral worth, democratic socialists also fight against oppression based on race, gender, sexuality, nationality and more. We do not reduce all forms of oppression to the economic; economic democracy is important, but we also need strong legal and cultural guarantees against other forms of undemocratic domination and exclusion.

What socialism can do for you

The United States has a rich—but hidden—socialist history. Socialists and Communists played a key role in organizing the industrial unions in the 1930s and in building the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s; Martin Luther King Jr. identified as a democratic socialist; Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, the two key organizers of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom were both members of the Socialist Party. Not only did Socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs receive roughly 6 percent of the vote for president in 1912, but on the eve of U.S. entry into World War I, members of the Socialist Party held 1,200 public offices in 340 cities. They served as mayors of 79 cities in 24 states, including Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Reading, Penn., and Buffalo.

Brutally repressed by the federal government for opposing World War I and later by the Cold War hysteria of the McCarthy era, socialists never regained comparable influence. But as organizers and thinkers they have always played a significant role in social movements. The real legacy of the last significant socialist campaigns for president, those of Eugene V. Debs and Norman Thomas, is how the major parties, especially the Democrats, co-opted their calls for workers’ rights, the regulation of corporate excess and the establishment of social insurance programs.

As the erosion of the liberal and social democratic gains of the post-World War II era throughout the United States, Europe and elsewhere shows, absent greater democratic control over the economy, capital will always work to erode the gains made by working people. This inability to gain greater democratic control over capital may be a contributing factor to why the emerging social movements resisting oligarchic domination have a “flash”-like character. They erupt and raise crucial issues, but as the neoliberal state rarely grants concessions to these movements, they often fade in strength. Winning concrete reforms tends to empower social movements; the failure to improve the lives of their participants usually leads these movements to dissipate.

In the United States, nascent movements like Occupy Wall Street, the

Fight for 15,

Black Lives Matter and

350.org have won notable reforms. But few flash movements have succeeded in enacting systemic change. Only the revival of a decimated labor movement and the rebirth of governing socialist political parties could result in the major redistribution of wealth and power that would allow real change on these issues.

For all their problems—and there are many—this is the promise of European parties like Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain. But the Syriza government retreated back to austerity policies, in part because Northern European socialist leaders failed to abandon their support for austerity. The election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the British Labour Party may represent the first step in rank-and-file socialists breaking with “third way” neo-liberal leadership.

Is Bernie really a socialist?

For Sanders, “democratic socialism” is a byword for what is needed to unseat the oligarchs who rule this new Gilded Age. In his much-anticipated

Georgetown speech, Sanders defined democratic socialism as “a government which works for all of the American people, not just powerful special interests.” Aligning himself with the liberal social welfare policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson, Sanders called for restoring progressive income and strict corporate taxation to fund Medicare for All, paid parental leave, publicly financed child care and tuition-free public higher education.

Yet he backed away from some basic tenets of democratic socialism. He told the audience, “I don’t believe the government should take over the grocery store down the street or own the means of production.” But democratic socialists want to democratize decisions over what we make, how we make it and who controls the social surplus.

In truth, Sanders is campaigning more as a social democrat than as a democratic socialist. While social democrats and democratic socialists share a number of political goals, they also differ on some key questions of what an ideal society would look like and how we can get there. Democratic socialists ultimately want to abolish capitalism; most traditional social democrats favor a government-regulated capitalist economy that includes strong labor rights, full employment policies and progressive taxation that funds a robust welfare state.

So why doesn’t Sanders simply call himself a New Deal or Great Society liberal or (in today’s terms) a “progressive”? In part, because he cannot run from the democratic socialist label that he has proudly worn throughout his political career. As recently as 1988, as mayor of Burlington, Vt.,

he stated that he desired a society “where human beings can own the means of production and work together rather than having to work as semi-slaves to other people who can hire and fire.”

But today, Sanders is running to win, and invoking the welfare state accomplishments of FDR and LBJ plays better with the electorate and the mainstream media than referencing iconic American socialists like Eugene V. Debs. In his Georgetown speech, Sanders relied less on references to Denmark and Sweden; rather, he channeled FDR’s 1944 State of the Union address in which he called for an Economic Bill of Rights, saying, “true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. 'Necessitous men are not free men.'”

Sanders’ campaign rhetoric does occasionally stray into more explicitly democratic socialist territory, though. He understands the nature of class conflict between workers and the corporate moguls. Unlike most liberals, Sanders recognizes that power relations between the rich and the rest of us determine policy outcomes. He believes progressive change will not occur absent a revival of the labor movement and other grassroots movements for social justice. And while Sanders’ platform calls primarily for government to heal the ravages of unrestrained capitalism, it also includes more radical reforms that shift control over capital from corporations to social ownership: a proposal for federal financial aid to workers’ cooperatives, a public infrastructure investment of $1 trillion over five years to create 13 million public jobs, and the creation of a postal banking system to provide low-cost financial services to people presently exploited by check-cashing services and payday lenders.

Harnessing the socialist energy

While Sanders is not running a full bore democratic socialist campaign, socialists must not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. The Sanders campaign represents the most explicit anticorporate, radical campaign for the U.S. presidency in decades. Thus the

Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), of which I am a vice-chair, is running an “

independent expenditure campaign” (uncoordinated with the official campaign) that aims to build the movement around Sanders—and its “political revolution”—over the long run.

For us, even if Sanders’ platform isn’t fully socialist, his campaign is a gift from the socialist gods. In just six months, Sanders has received campaign contributions from 800,000 individuals, signed up tens of thousands of campaign workers and introduced the term “democratic socialism” and a social democratic program to tens of millions of Americans who wouldn’t know the difference between Trotsky and a tchotchke. Since the start of the Sanders campaign, the number of people joining DSA each month has more than doubled.

Though elected to both the House and Senate as an independent, Sanders chose to run in the Democratic presidential primary because he understood he would reach a national audience in the widely viewed debates and garner far more votes in the Democratic primaries than he would as an independent in the general election. The people most vulnerable to wall-to-wall Republican rule (women, trade unionists, people of color) simply won’t “waste” their votes on third-party candidates in contested states in a presidential election.

The mere fact of a socialist in the Democratic primary debates has created unprecedented new conversations. Anderson Cooper’s initial question to Sanders in the first Democratic presidential debate, in front of 15 million viewers, implicitly tried to red-bait him by asking, “How can any kind of a socialist win a general election in the United States?” The question led to a lengthy discussion among the candidates as to whether democratic socialism or capitalism promised a more just society. When has the capitalist nature of our society last been challenged in a major presidential forum?

Yet without a major shift in sentiment among voters of color and women, Sanders is unlikely to win the nomination. Sanders enthusiasts, who are mostly white, have to focus their efforts on expanding the racial base of the campaign. But, regardless of who wins the nomination, Sanders will leave behind him a transformed political landscape. His tactical decision to run as a Democrat has the potential to further divide Democrats between elites who accommodate themselves to neoliberalism and the populist “democratic” wing of the party.

Today, Democrats are divided between affluent, suburban social liberals who are economically moderate—even pro-corporate—and an urban, youth, black, Latino, Asian American, Native American and trade union base that favors more social democratic policies. Over the past 30 years, the national Democratic leadership—Bill Clinton, Rahm Emanuel, Debbie Wasserman Schultz—has moved the party in a decidedly pro-corporate, free-trade direction to cultivate wealthy donors. Sanders’ rise represents the revolt of the party’s rank and file against this corporate-friendly establishment.

Successful Left independent or third-party candidates invariably have to garner support from the same constituencies that progressive Democrats depend on, and almost all third-party victories in the United States occur in local non-partisan races. There are only a few dozen third-party members out of the nearly 7,400 state legislators in the United States.

Kshama Sawant, a member of Socialist Alternative, has won twice in Seattle’s non-partisan city council race, drawing strong backing from unions and left-leaning Democratic activists (and some Democratic elected officials). But given state government’s major role in funding public works, social democracy cannot be achieved in any one city.

The party that rules state government profoundly affects what is possible at the municipal level. My recollection is that in the 1970s and 1980s, DSA (and one of its predecessor organizations, the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee) had more than 30 members who were elected members of state legislatures or city councils. Almost all of those socialist officials first won Democratic primaries against conservative Democratic opponents. In the seven states (most notably in New York, Connecticut and Oregon) where third parties can combine their votes with major party lines, the

Working Families Party has tried to develop an “inside-outside,” “fusion” strategy vis-a-vis the Democrats. But the Democratic corporate establishment will never fear progressive electoral activists unless they are willing to punish pro-corporate Democrats by either challenging them in primaries or withholding support in general elections.

The tragedy of Jesse Jackson’s 1988 campaign was that despite winning 7 million votes from voters of color, trade unionists and white progressives, the campaign failed to turn its Rainbow Coalition into an electoral organization that could continue the campaign’s fight for racial and economic justice. This lesson is not lost on Sanders; he clearly understands that his campaign must survive his presidential bid.

As In These Times went to press, the Sanders campaign only has official staff in the early primary states of New Hampshire, Iowa, South Carolina and Nevada. Consequently, the Sanders movement is extremely decentralized, and driven by volunteers and social media. Only if these local activists are able to create multi-racial progressive coalitions and organizations that outlast the campaign can Sanders’ call for political revolution be realized.

Campaign organizations themselves rarely build democratic, grassroots organizations that persist after the election (see Obama’s Organizing for America). Sanders activists must keep this in mind and ask themselves: “What can we do in our locality to build the political revolution?” The Right still dominates politics at the state and local level; thus, Sanders activists can play a particularly crucial role in the 24 states where Republicans control all three branches of the government.

Embracing the ‘s’ word

Sanders has captivated the attention of America’s youth. He has generated a national conversation about democratic socialist values and social democratic policies. Sanders understands that to win such programs will take the revival of mass movements for low wage justice, immigrant rights, environmental sustainability and racial equality. To build an independent left that operates electorally both inside and outside the Democratic Party, the Sanders campaign—and socialists—must bring together white progressives with activists of color and progressive trade unionists. The ultimate logic of such a politics is the socialist demand for workers’ rights and greater democratic control over investment.

If Sanders’ call for a political revolution is to be sustained, then his campaign must give rise to a stronger organization of long-distance runners for democracy—a vibrant U.S. democratic socialist movement. Electoral campaigns can mobilize people and alter political discourse, but engaged citizens can spark a revolution only if they build social movements and the political institutions and organizations that sustain political work over the long-term.

And because anti-socialism is the ideology that bipartisan political elites deploy to rule out any reforms that limit the prerogatives of capital, now is the time for socialists to come out of the closet. Sanders running in the Democratic primaries provides an opportunity for socialists to do just that, and for the broad Left to gain strength. If and when socialism becomes a legitimate part of mainstream U.S. politics, only then will the political revolution begin.